Toitanga

Kate Rowland Heretaunga

-

Tauira / Student

Kate Rowland -

Kaitautoko / Contributor

Niwa Brightwell -

Kaiako / Lecturers

Tanya Ruka, Simon Fraser, Jeongbin Ok

-

School

Te Herenga Waka (Victoria University of Wellington)

Description:

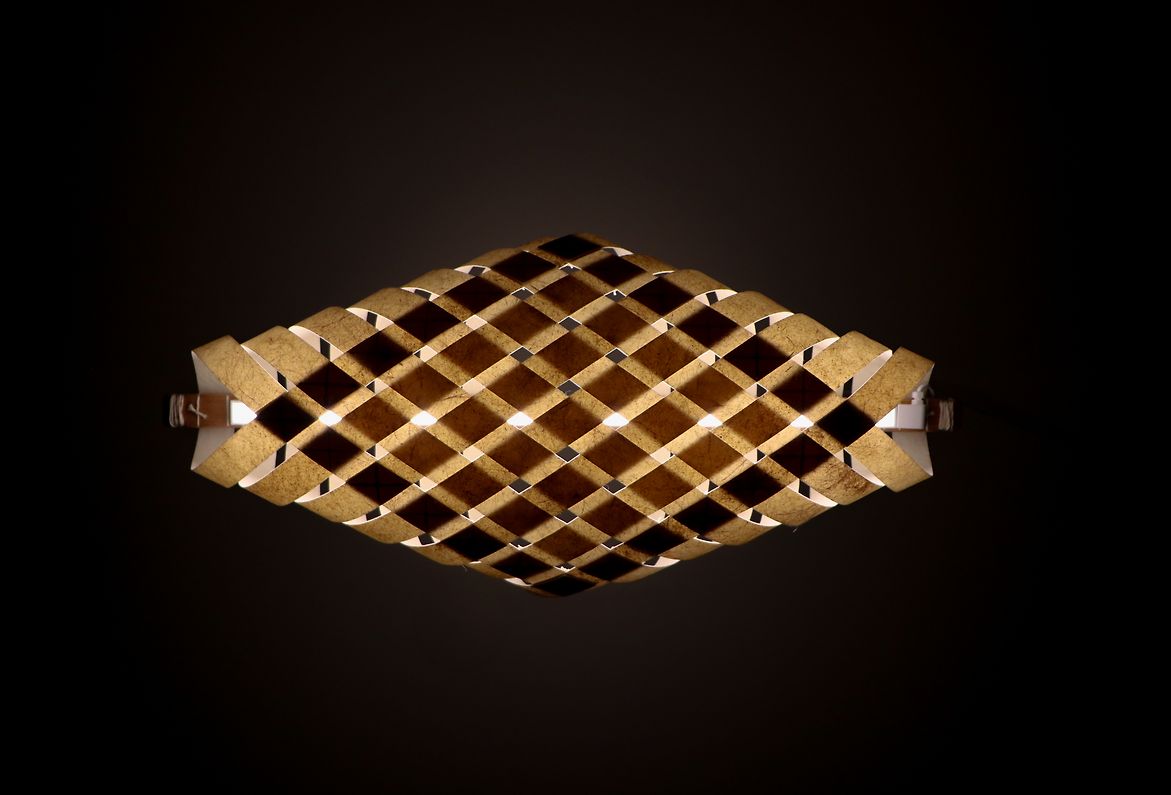

This project explores the intersection of cultural reconnection, sustainable design, and material innovation through the creation of a single light. Developed as part of my Master’s research, the work reflects my journey to reconnect with my Māori whakapapa and to ground my design practice in tikanga Māori. The light is not just an object, but a vessel for story, one that weaves together place, people, and process.

Based in Heretaunga (Hastings), where I grew up, the research began with a deep curiosity about the plants native to that landscape. The project explored how local taonga species such as harakeke, tī kōuka, and raupō could be reimagined not only as materials but as knowledge holders and collaborators in a design process guided by Mātauranga Māori. Rather than extracting value, the work asked: how might design honour the whakapapa of these fibres? How can we create materials and outcomes that reflect cultural values and ecological care?

The process was rooted in hands-on experimentation with these native resources, alongside learning from weavers and material experts. Through mentorship and kōrero, I was guided in traditional fibre practices, harvesting protocols, and the deeper meanings embedded in material use. Tikanga shaped each step, from how I sourced and processed harakeke to how I used modern tools like heat pressing and laser cutting with care and purpose.

One key outcome was the development of a biodegradable composite made from harakeke fibre and a plant-based biopolymer. The result is a material that performs sustainably and carries cultural integrity, designed to break down and return to the whenua. The final light combines two versions of this material: one from stripped fibre and one from leaf offcuts gifted by weavers. Their layered composition reflects overlapping knowledge systems, practices, and identities.

Rather than forcing these materials into rigid forms, I let their natural properties guide the structure. The name Heretaunga translates to “to tie up” and “a mooring place of canoes,” a place of return and belonging. This meaning guided both the conceptual and physical form of the design. The light takes on the elongated, symmetrical shape of a waka, symbolising both voyaging and return. It grounds the work in the place where materials were gathered and tikanga was learned.

The light was assembled through binding and weaving, guided by the techniques of raranga. It is held together with muka lashings, stripped and twisted by hand using traditional miro methods. These lashings are functional and symbolic, echoing the idea of tying together people, land, and practice.

This work proposes a design approach where Indigenous methodologies are foundational. It contributes to conversations around sustainability, Indigenous sovereignty, and material innovation by showing what becomes possible when we design through relationship, with people, with whenua, and with fibre. I have come to understand that material is not just what we shape. It is what shapes us.

Judge's comments:

A beautiful artefact, acting as a vessel to hold narrative and origin. Materiality and form are brought to life through light, making this piece truly shine. It is deserving of gold at this year’s Best Awards. He rawe te mahi – well done.